Image by Eric Perlin from Pixabay

There is a lot of “free money” to be earned through the PC Optimum program.

We’ve previously discussed quite a bit about how to maximize your points through various strategies, and on the surface all looks pretty good. Unfortunately it’s not all sunshine and roses. There’s another hidden problem that we have not yet addressed, but which I alluded to very briefly at the end of Part 2.

What happens to the value of your points if the item that you purchased to earn those points was significantly marked up to begin with? And what if other competitor stores were selling that item for cheaper? Would you still be getting those super higher return rates? Or is it all just a mirage, designed to fool you into monetary submission. And how do we figure out if we’re actually getting free money, or if we’re just receiving another hollow promise?

We’re going on another deep dive of this topic, and to help us out, I’m going to use something I like to call, the Rule of Averages.

Recap

In Part 3 of the PC Optimum Series, we dug into how you can capitalize on the points you earn, as well as maximize their redeemed value. We defined the “returns” of the program as “real cash back” (RCB) to more easily and accurately assess the true value of the PC points program.

Ultimately, it’s very easy to achieve a baseline real cash back return of 23% on your purchases, which is relatively unheard for any other reward program. This can be accomplished by using the 20x points events and redeeming points at their standard value. However, by implementing additional strategies, we were easily able to bump up the return to at least 39%. “Good” cash-back credit cards on the other hand only provide ~3 -5% returns.

This all sounds pretty awesome considering the massive amount of “free” money you end up getting to spend. But as I mentioned above, all may not be as it seems.

When 30 is not worth 30

Shoppers Drug Mart (SDM) is where it’s at to get these super high return rates. Even though SDM has these insane points offers that seem to provide an incredible monetary value, they are also well known for being quite pricey. The bottom line is that whatever cash back return you do end up getting, will be eaten away by the amount that you overpaid for the item which you bought.

Let’s say you make a $100 purchase at SDM on a 20x the points day. This will net you 30,000 pts which is good for redeeming $30 of “free” merchandise at the base redemption level. In total, you have obtained $130 worth of goods but you’re only out of pocket $100.

But what if you can get that same $130 amount of goods for $100 somewhere else – say, No Frills, or Walmart? Well, then those 30,000 pts from SDM are basically worthless. This is because what you actually did was buy groceries that were overpriced by $30, and SDM gave you back the amount that you overpaid.

This is why the PC optimum program is so successful, because it gives the near perfect illusion of getting a tremendous value when the truth is not in fact so.

If we explore a bit deeper with this idea and are able to find those $130 of SDM goods for a price of less than $100 elsewhere, then you’re not even breaking even with PC Points anymore. You’ve actually paid a premium on those groceries, and hence, lost money, and time!

The key to this puzzle lies in the opposite direction.

If you are able to purchase $130 of SDM groceries for only $100, but you cannot find that same amount of groceries elsewhere for less than $130, that’s when your 30,000 bonus points is actually worth a true $30.

The Rule of Averages

There are a number of different methods for both collecting and redeeming points, each with differing valuations. Thus it can be challenging to figure out what you are actually getting out of the PC Points program and whether any of that “free money” is actually “free”.

Part 3 of the this series addressed entire SDM purchases as a whole that were completed during points events, and determined the real cash back return you received from those transactions. While this is very helpful, it’s only applicable from the basic and general monetary viewpoint of “Spend X and get Y back”. It will tell you nothing about if X was vastly over priced to begin with. This is where the Rule of Averages comes in.

The basic premise and application for this rule is to extrapolate the price that you paid for a single item over time, as well as the amount of points that you earned and redeemed for that item over time too. These two parts are then combined into an average to determine how much that item really costed you out of pocket. That average is then compared to the lowest sales price at other stores to ultimately find out if you are over or underpaying for that item. What we’re doing here is similar to how we calculated real cash back returns in Part 3, but for specific items this time instead of entire purchases.

The PB Experiment

To illustrate this in practice, I’ll be using a 1kg jar of peanut butter. Why peanut butter? Because it’s sterile, and I like the taste! It’s also easily available and has lots of protein.

We’ll also be taking the following variables into account for simplicity purposes.

- You are shopping at a 20x points event

- Bonus points you earned at that specific event will be redeemed at face value

- We are excluding any extra points strategies (ie: PC Mastercards, gift cards, etc).

So let’s say you really like peanut butter just as much as I do. But so much so that you went to the 20x the points event and purchased $100 of peanut butter!!! The majority of the time, SDM lists 1kg jars of PB (Kraft) for $4.00. In total you bought yourself 25 jars worth! Because you spent $100, you also received 30,000 points, which you then went on to use to buy $30 more of peanut butter, also at $4.00 a kilogram. This adds another 7.5 jars of peanut butter for a grand total of 32.5 jars. (I’m aware you can’t buy 1/2 jars, but bear with me)

If you average out how much you paid out of pocket versus how many jars you received (both paid and “free”), you will end up an average value per 1kg jar of $3.08 ($100 / 32.5 jars).

Now that we have the combined average value of the peanut butter we bought, we can now compare it to common low prices at other stores. By “common” I mean that the item goes on sale frequently at stores for a regular low price. In my area, the lowest common sales price I’ve seen for 1kg of Peanut butter is $3.00 at places like Walmart and No Frills.

So, this means that in this particular situation, even though you were able to buy PB at SDM for an average of $3.08 by using the PC Points program, you still overpaid if it’s being sold for $3.00 somewhere else. What this also means, is that not only did you waste your time trying to collect points at SDM, but that $30 of “Free” PB was just an illusion and its value quickly went up in smoke and has become worthless. You might as well have just skipped the 20x the points and went straight to the other store where PB was $3.00 per jar.

To truly have gotten the full $30 worth of free peanut butter at SDM, you would have needed to originally purchase the $100 of PB at SDM for a listed price of $3.00 per jar and also redeemed your “free” $30 for $3.00 per jar, bringing the overall average cost down to $2.31 per jar. This is how you actually get free money out of PC Points Program. Every cent that you pay above the $2.31 average eats away at your “free” $30, until it’s completely gone at at $3.89 per jar.

The same idea goes from a real cash back return perspective. For every cent that you go above $2.31 will slowly destroy your 23% return until it reaches 0% at $3.89. And in fact, if you go higher than $3.89, well, you’re now into the negative returns… Oh boy!

You can substitute in any item you like instead of peanut butter to see what it’s truly worth. Just make sure you know how much things are listed for on a regular basis at other grocery stores.

Now this is just an example, as I don’t expect anyone to go out and buy $100 of peanut butter in a single purchase. But the point is that over time, you will buy individual items numerous times. If you frame a single purchase of any item as part of the overall average for all future purchases of the same item, this is where the extrapolation allows you to determine that item’s on the spot true value and what it’s really costing you.

A Quicker Way to Determine on the spot Value

No one is going to take the time to calculate peanut butter this way, or any other item for that matter. Well, maybe people like me, but in general, no. I get it. It’s a bit nutty (pun intended). I mean, you’d have to have a whole piece of foolscap with you plus a pencil, eraser, and time!! It’s kind of like when you took high school math, and the teacher showed you how they came up with a math formula via a pre-formula, even though that pre-formula was completely useless as practical information. So, with that being said, on to a prettier and more condensed equation! We’ll be looking at how to find an item’s true discount sales price, which is just the average out of pocket cost that an item is worth when factoring in the value of your PC points. This is not the item’s listed “on the shelf” price.

Item’s True Discount Sales Price Formula (*for non-taxed items):

(A) Item’s Listed Price = $__

(B) Discount = __real cash back % (see chart below)

(C) Amount off purchase price = A x B

(D) Item’s new price = A - C

(E) Percentage Paid of Full Price = D / A

(F) An Item’s true discount sales price = A x E-(B) is predetermined based on the points strategies you use

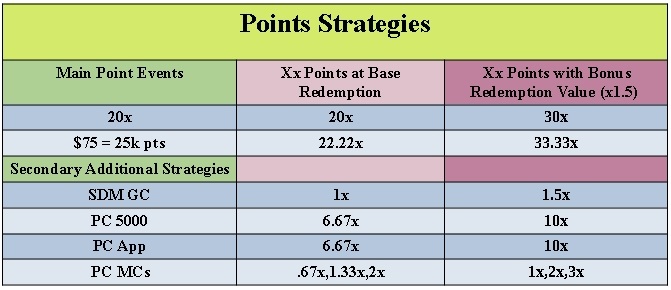

To find your (B) variable, we need to first use the below Points Strategies chart to determine and add together which point strategies you plan on using and how many “times the points” (or Xx) they’re worth. For our peanut butter example, we bought our PB during a 20x the points event, and redeemed the points at the base redemption value. Therefore, the chart tells us that this particular strategy provides 20x the points. (Typically, someone’s individual strategy(s) won’t change very often, so you should not need to reference this chart too frequently). If we had also used the PC 5000 strategy, then we would have had 26.67x the points (20x + 6.67x).

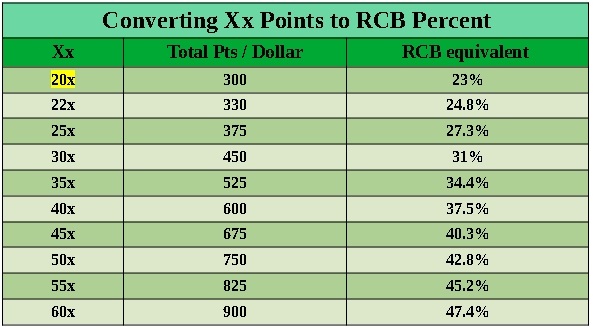

Once we’ve determined how many Xx points our strategy provides, we can then move on to the next chart, Converting Xx Points to RCB Percent, and plug in our 20x to find out the equivalent Real Cash Back value. In our case, 20x the points is worth 23% RCB.

Now we have our (B) variable to plug in to the equation. Thus, still using our peanut butter example at $4.00/kg:

(A) Item’s Listed Price = $ 4.00

(B) Discount = 23%

(C) Amount off purchase price = $4.00 x 0.23 = $0.92

(D) Item’s new price = $4.00 - $0.92 = $3.08

(E) Percentage Paid of Full Price = $3.08 / $4.00 = 77%

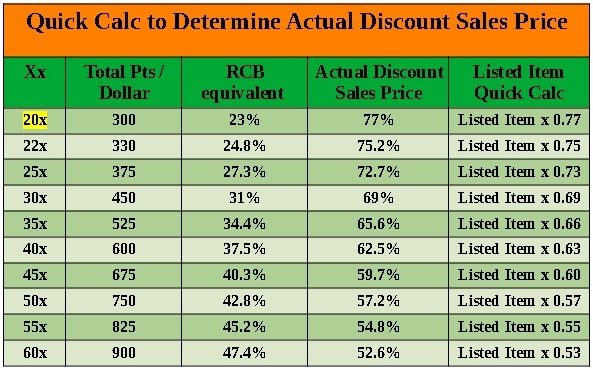

(F) An Item’s true discount sales price = $4.00 x 0.77 = $3.08Of course, even with the condensed equation, no one has time to go through the above calculation for each and every item. An even quicker way is to just multiply any item’s listed price by the percentage paid of full price (E). As long as you know what points strategy you’re using, based on the charts above, it’s relatively simple because (E) remains constant based on that particular strategy.

So, in our PB example, our selected points strategy provides 23% RCB. This also means that you’re only paying 77% (E) of the item’s full price. The key here is that the discount/RCB percent (B) and the discounted sales price percentage (E) are intertwined and always add up to 100%. They’re the inverse of each other.

You can apply this 77% by multiplying it against any listed item’s price determine its true price, as long as your points strategy doesn’t change.

If your points strategy changed to a RCB of let’s say 40%, then you know that you’re only paying 60% full price for an item, and therefore can just multiply that item’s list price by 0.60 to quickly determine how much that item is actually costing you. It’s that easy.

I’ve summarized these quick calculations in the chart below:

If you happen to already be at a competing store, you can do the calculation in reverse. Instead of multiplying a competitor’s item by 77%, you can divide it by 77%. Let’s say Walmart sells PB for $3.50. Divide this by 77% results in $4.50.

Because we know that SDM regularly sells PB for $4.00, this means that the Walmart price is still overpriced, and we’d be better off buying the PB at SDM instead.

So the moral of the story is if the SDM listed price of an item is almost at or lower than the lowest common price for the same item elsewhere, then buy as much of it as you can, because that’s where the real “Free” money is.

A note on Extrapolation:

Peanut butter is not always $4.00 per 1Kg at SDM. Occasionally I’ve seen it listed at almost $10/kg during some bonus points and redemption events. Many items are often not on sale during redemption events either, and even price inflated on purpose during these times to erode your bonus points’ purchasing power. If you go into a redemption event viewing all your points as “Free” money and buy things regardless of their prices, that “free” money quickly evaporates the more over-priced an item becomes.

Personally, I would never pay $10/kg for PB. But $4 is decent. I might even go up to $5 if I was really desperate, as $5 multiplied by 77% is still only an average of $3.85 per 1kg. Not the cheapest I’ve ever seen, but still a very solid price for PB. The point is, to use the PC Points program effectively, you should do your best to buy things that are at the lowest price point possible, especially when compared to other stores. Otherwise, the higher the prices get, the lower your returns become until they reach zero, or even negative.

Why Use Equivalent buying and redemption pricing? (Ie: $4 buy, $4 redeem)

For one thing, it makes the math for the rule of averages much easier, quicker, and more consistent. It also helps reinforce the idea of buying as low as possible to maximize return. The more important of the two factors is the “buying” part because that is where the actual “out of pocket” expense occurs. It’s also the largest monetary value of the two, thus it plays the most significant part in overall return.

Equivalent pricing also demonstrates that each individual item purchased actually matters significantly when they are extrapolated over the course of many small purchases. It’s not that everyone is going to buy $100 of peanut butter all at once. It’s more the idea of is that one jar you’re buying an actual deal or not if you buy it at the listed price over multiple different occasions. Is it ok to buy something that is really overpriced to begin with? Sure that’s fine. I just wouldn’t make a habit of it. Or else you’re defeating the whole purpose of the PC points program, which is to get actual free money, and hence free groceries.

In real practice, your entire purchase would be combined of many different items. Some may have a true value that’s below the common sales price elsewhere, and some may have a higher value than that. Just know that each time you add something to your cart that has a higher value than some other store, your return is slowly eaten away.

On another note, if you’re always buying something out of pocket at a hyper inflated price, then it doesn’t really matter what the redemption prices are. The value is gone from the points system. If you bought at a low price, the higher your redeemed item’s listed price gets, the lower your return will be.

Ultimately, any return only exists if the item’s average price works out to be equivalent to or lower than a comparable price somewhere else. I make a habit to only buy stuff at SDM when they’re on sale anyway. As my mom says, never pay full price for anything!

Taxes

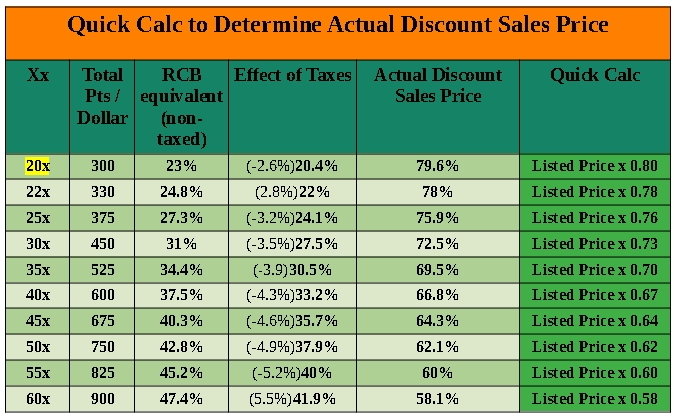

How do taxes come in to play with all this? In Part 3, I mentioned that taxes reduce your real cash back return between approximately 2.5% and 5%. For example, when using a 20x the points event with basic point redemption value, instead of receiving 23% RCB, you’d take a 2.5% hit, ending up with ~20.5% RCB return. This is the same as a paying a discounted sales price of 79.5%. How did we determine this outcome?

Calculating With Taxes

To find out how taxes affect RCB return, real average cost, and discount sales price, look at the following the scenario.

Scenario: We want to go buy some delicious, crunchy (and taxable) Doritos. So we’re attending a 20x points event to buy $100 of Doritos at $4/bag. Then at a later date, we’ll redeem the $30 of received bonus points at regular redemption value, for $4/bag.

To Determine Real Cash Back Return

$100 of Doritos / $4 = 25 bags of Doritos

Tax (HST) on $100 = $13

Total spent out of pocket = $113

20x points on $100 = 30,000pts ($30).

$30 / $4 = 7.5 bags of Doritos

Tax (HST) on $30 = $3.90

–Total value of goods and tax = $100 + $13 + $30 + $3.90 = $146.90

-Total points redeemed ($30) / Total value of goods ($146.90) = 20.5% RCB return. This equivalent to a discount sales price of 79.5%

Now, we’re going to find out the real average cost per bag of Doritos, based on 32.5 total bags:

Total spent out of pocket = $100 + 13 (HST) + 3.90 (HST) = $116.90

Average value per bag = $116.90 / 32.5 bags = $3.60 post tax.

$3.60 / 1.13 (13% HST) = $3.18 Pre tax

The Quick Way: Using the Discount Sales Price

Multiply $4 bag of Doritos by the discount sales price of 79.5% = $3.18 pre-tax

I’ve pre-calculated a bunch of the different combinations of points strategies as affected by taxes, easily referenced in the Quick Calc chart below. (*Light rounding as been applied)

Strategies of Value

The tax effect chart represents the worst case scenarios, as you won’t likely have an entire grocery haul comprised of 100% taxable items. It will be a combination of taxed and non-taxed groceries, therefore the return will be somewhere in between. The Canada Revenue Agency defines what qualifies as a taxable grocery item or not. More info on this can be found here.

The best overall strategy (which I prefer) is using the 20x points combined with the PC Mastercard, and redeeming points during a bonus points event. This yields RCB returns of 33% from non-taxed items and 29% from taxable items. Their respective quick calcs are 0.69 and 0.71.

You can technically improve all the way up to only paying 55% (non-taxed) and 60% (taxed) of full price, but that’s using the more tedious strategies which I don’t believe are really worth the time or effort.

Conclusion

Looks can be deceiving. In the case of PC Optimum Points Program, this is definitely so. Yes, the rewards looks high! 39% cash back in the form of “free money” sounds pretty sweet. I always shake my head whenever I see PC’s ad stating “Every 10,000 points is like $10 of free stuff”. My goal is to help you go from “is like $10”, to “actually getting $10” of free stuff.

But to truly achieve the “free money” advertised, you’ll need to endeavor to maximize the PC program as much as possible. I’m also aware that I’ve been drilling it in pretty hard about trying to buy low as often as possible, but that’s because it’s the only realistic way to really reap the maximum benefit of the PC Optimum Program.

There are a lot of charts and calculations that we used for the Rule of Averages. I know. I put them there. 🙂

But it can all be summed up in the following four steps.

Step 1: Review the Points Strategies chart to figure out how many

Xx points you’re getting based on your strategies of choice. This usually

won’t change much once you’ve established the route you’re taking.

Step 2: Plug in your Xx points number into the Quick Calc Actual Discount

Sales Price charts for non-taxed and taxed items to determine the respective quick calcs you’ll be using. This step is based on Step 1, thus also won’t change

often once established.

Step 3: Use your quick calc numbers on listed items’ prices in store to find

they’re real true value.

Step 4: Compare the real true value to sales prices of other stores to know if you’re actually getting free money back from what you’re purchasing. The closer you get to buying SDM items at the lowest common sales price of other stores, the higher return you’ll net. Repeat steps 3 and 4.

Applying the Rule of Averages will help provide you with more insight and empowerment in regards to the choices you make at SDM, by figuring out any item’s on the spot true value, and whether that item was vastly overpriced to begin with. It will assist you in determining the value you’re actually getting out of the PC Optimum program, thus helping to keep your pockets full of change.